Hover over or click on an image for details and new Reduced Pricing.

Price $2,350- Reduced Price:

$1,645– SOLD

Price $575- Reduced Price:

$395-

Price $550- Reduced Price:

$395-

$395-

$395-

$395-

$395-

$395-

$395-

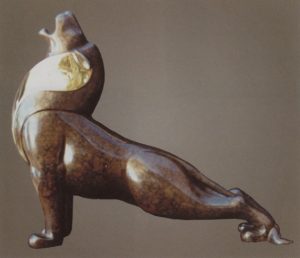

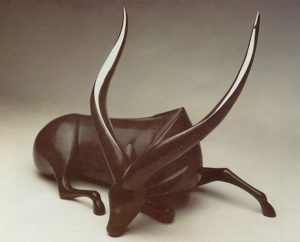

Loet Vanderveen brings an incredible sympathy to every animal he creates. His sculptures capture an animal’s signature pose and freeze it in time, revealing the essence not only of its form, but also its way of moving. Vanderveen researches his subjects exhaustively and has been on many African safaris to gather first-hand impressions.

As a young boy in Rotterdam, Holland, Loet Vanderveen went nearly every day to the city’s Victorian-era zoo. “I thought animals were way beyond belief. I marveled at them,” says the artist. The zookeepers gave him free run of the place and let him help care for the animals. “They had a little lion cub and I would feed it practically every day. Then he grew up and they put him in a cage-and I was heartbroken.”

More heartbreak was in store for the young vnaderveen. On May 14th, 1940, the Germans bombed Rotterdam, killing 617 people and virtually flattening the city. When warned of the coming attack, the government ordered the Dutch army to shoot the animals in his beloved zoo, fearing that they’d get loose and endanger the populace. “I got there right after the bombardment,” says Vanderveen, “and whole place was in ruins. The lions and big cats-many of them were shot. But in the midst of it all, there was one elephant roaming. It was very, very poetic.” Among all the stories of death and destruction, there were also some amazing stories of survival.

As a young boy in Rotterdam, Holland, Loet Vanderveen went nearly every day to the city’s Victorian-era zoo. “I thought animals were way beyond belief. I marveled at them,” says the artist. The zookeepers gave him free run of the place and let him help care for the animals. “They had a little lion cub and I would feed it practically every day. Then he grew up and they put him in a cage-and I was heartbroken.”

More heartbreak was in store for the young vnaderveen. On May 14th, 1940, the Germans bombed Rotterdam, killing 617 people and virtually flattening the city. When warned of the coming attack, the government ordered the Dutch army to shoot the animals in his beloved zoo, fearing that they’d get loose and endanger the populace. “I got there right after the bombardment,” says Vanderveen, “and whole place was in ruins. The lions and big cats-many of them were shot. But in the midst of it all, there was one elephant roaming. It was very, very poetic.” Among all the stories of death and destruction, there were also some amazing stories of survival.

The zoo’s chimpanzee somehow escaped and turned up later in a local bar. A seal was blown out of its pool and ended up in a canal in the city. But Loet Vanderveen’s life would never be the same.

The young boy was completely alone. His mother had died in a car accident when he was eight, and shortly after the bombing his father died of a staph infection when no medicine was available to treat him. With his half-Jewish heritage, it became imperative for Loet to get out of occupied Holland. He set off on his bicycle and escaped over the Belgian border. When he arrived in France, he was arrested by the Germans and spent three weeks in prison. After his release he joined the Dutch army and was decorated for valor by Queen Wilhelmina.

Post-war times were chaotic, but the young man had friends in the fashion industry who found him work doing sketches for designers. Loet went to Paris hoping to be a designer himself, but was only offered a job sketching by a young Christian Dior. He turned it down, “…like an idiot. It was one of the biggest mistakes I ever made.”

He did find work in London designing sportswear until his American visa cleared and he packed for New York City. For three years he studied with a master ceramicist, learning the challenging art of reduced glazes.

The young boy was completely alone. His mother had died in a car accident when he was eight, and shortly after the bombing his father died of a staph infection when no medicine was available to treat him. With his half-Jewish heritage, it became imperative for Loet to get out of occupied Holland. He set off on his bicycle and escaped over the Belgian border. When he arrived in France, he was arrested by the Germans and spent three weeks in prison. After his release he joined the Dutch army and was decorated for valor by Queen Wilhelmina.

Post-war times were chaotic, but the young man had friends in the fashion industry who found him work doing sketches for designers. Loet went to Paris hoping to be a designer himself, but was only offered a job sketching by a young Christian Dior. He turned it down, “…like an idiot. It was one of the biggest mistakes I ever made.”

He did find work in London designing sportswear until his American visa cleared and he packed for New York City. For three years he studied with a master ceramicist, learning the challenging art of reduced glazes.

But the cutthroat business environment of the city wasn’t to his liking, and he and his new partner, the painter Alba Hayward, set out for California to find their paradise, settling on the rugged Big Sur coastline.They bought twenty acres 1600 feet above the surf and hired an architect who worked with Frank Lloyd Wright to build them a house. Loet built a large ceramic studio with kiln and spent the next years creating ceramic sculptures of animals, some with bronze tusks and horns.

In 1985 a lightning-sparked fire burned his house and studio to the ground. The only survivors were the rosebushes, some giant redwood trees and a few large ceramic pieces that Loet had dragged outside. Using the original plans, the house was rebuilt with improvements, but with a much smaller studio for sculpting the wax originals that his new bronze animals were being cast from.

This new medium brought Loet Vanderveen into the international spotlight. The combination of patina and polished bronze finishes added the finishing touch to his elegant sculptures. Works by Loet Vanderveen are now in the permanent exhibits of museums worldwide. Political figures, champions of sport, movie stars, wildlife organizations and heads of state-these diverse art collectors are united by an appreciation for the art of the Dutch boy who loved animals and grew up to be one of the most famous sculptors of our time.

In 1985 a lightning-sparked fire burned his house and studio to the ground. The only survivors were the rosebushes, some giant redwood trees and a few large ceramic pieces that Loet had dragged outside. Using the original plans, the house was rebuilt with improvements, but with a much smaller studio for sculpting the wax originals that his new bronze animals were being cast from.

This new medium brought Loet Vanderveen into the international spotlight. The combination of patina and polished bronze finishes added the finishing touch to his elegant sculptures. Works by Loet Vanderveen are now in the permanent exhibits of museums worldwide. Political figures, champions of sport, movie stars, wildlife organizations and heads of state-these diverse art collectors are united by an appreciation for the art of the Dutch boy who loved animals and grew up to be one of the most famous sculptors of our time.